By Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer

As an architect today you are expected to commit to sustainability and to have a “stance.” Society is asking this of us, our children are asking, our clients are asking. And our consciences even more so. That’s a good thing. Pressure shapes things.

But pressure can also lead to uniformity. All of the statements about sustainability and a better future that you find – and all too often don’t find – on today’s websites make it sound as though we know all there is to know. As if the catchwords “green,” “togetherness,” “dialog,” “inclusion,” “responsibility,” etc., alone will get the job done, provided we invoke them often enough. Notice the beautiful blooming roofs in our designs, observe the careful attention we pay to “spatial quality” and “microclimate,” see how we strive for fully flexible optimization, and sneer at all those cars in the city. I know that all of this is correct, but I don’t feel any conviction about it anymore, because I think all this just has to be in there. Because it all sounds so terribly interchangeable, self-evident, and well-rehearsed! But then, German architectural firms are so diverse and multifaceted. Just like the topic of sustainability itself. So shouldn’t taking a stance be an individual matter first – no matter how many people share it with me in the end?

In general terms, convergence in the biological sense means that living beings with similar environmental influences and functions develop similar, sometimes identical body shapes, although “the mere similarity of a trait doesn’t provide evidence of kinship” (Wikipedia). The shark and the dolphin have similar profiles, but no phylogenetic commonality. They’re completely different from a genetic point of view, yet from a distance they look almost the same. Only upon close observation is it clear that one has much nastier teeth.

What does stance have to do with body shape or deformation? Everything. After all, we’re talking about a quasi-orthopedic metaphor that “stands” for our attitude, to be precise. Stand up straight, child! Hold your head up, now! Be upright! Don’t hunch over in front of anyone, and have some backbone! If you don’t, you’ll always have to bend over and will be taken advantage of.

Of course I have a “stance.” And when I say “I,” most importantly I mean: we. Our office. The employees, the team, without whom the “I” that presumes to speak here on their behalf wouldn’t exist. And this is, of course, a presumption. Because in the first place, a stance can only be something personal. Of course I – as a private citizen acting on behalf of my children and my family, as well as a businessman representing my employees – want to live and design sustainably. But then again, who doesn’t want these things? All of us stand upright.

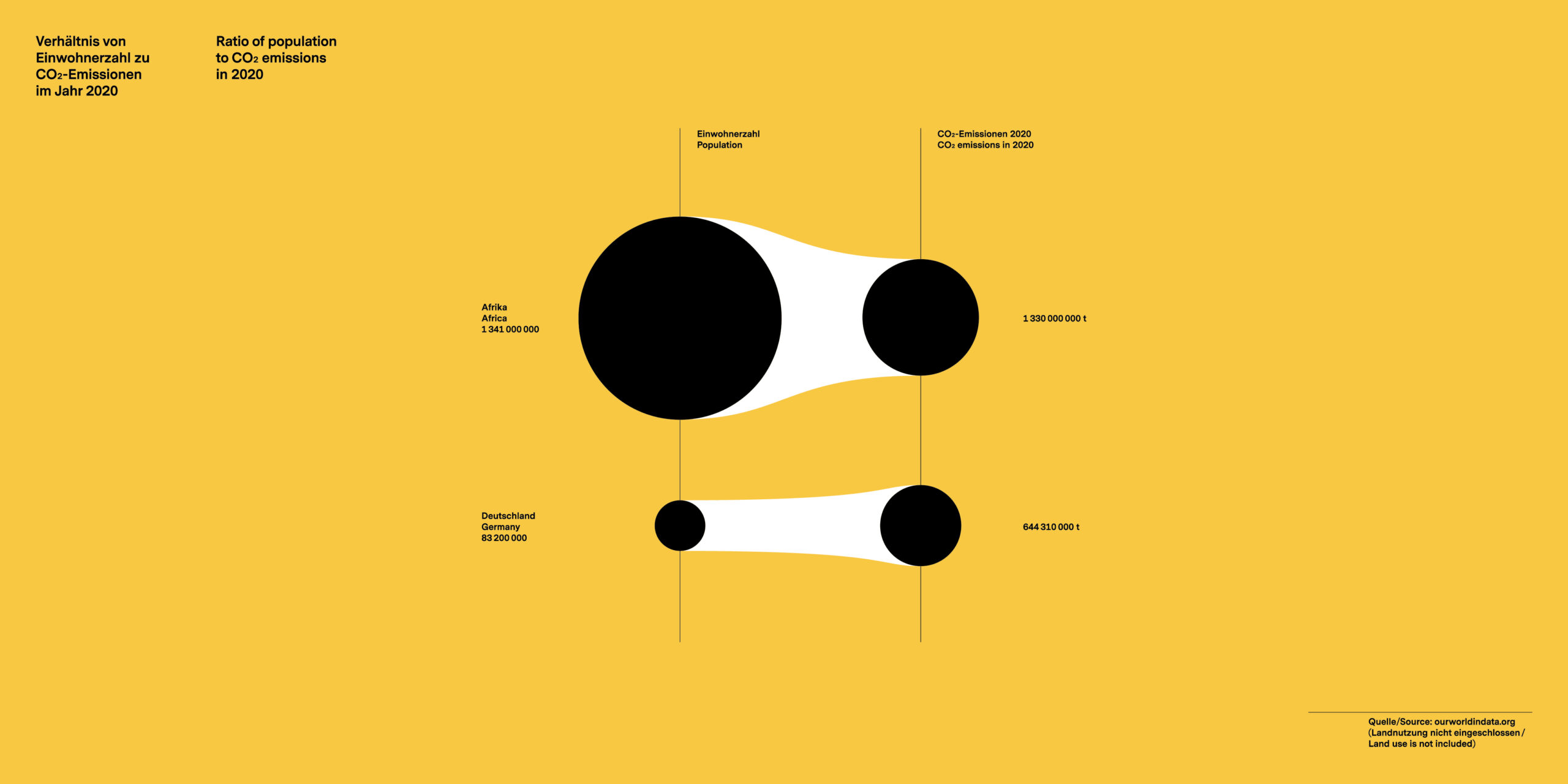

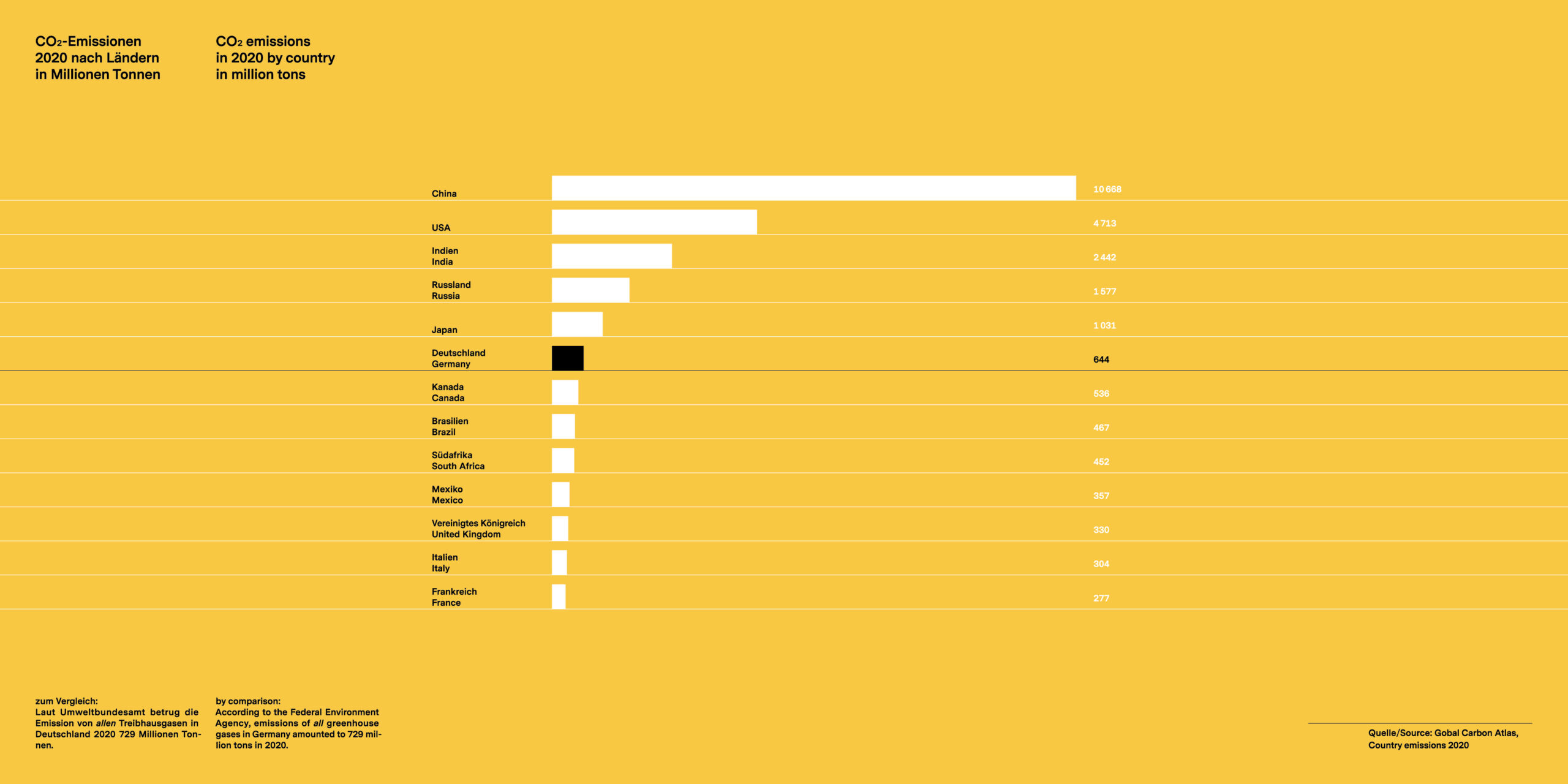

We’re all walking upright into a future that we, the privileged, we happy few, are screwing up – which we have been doing for decades, with our eyes wide open, in a nicely streamlined way. We’re coming from a guilty past that’s deforming the future. By global standards, Germany had emitted almost twice as much CO2 cumulatively than all of Africa by 2017. Or all of South America. In other words, Germany consumed as much as two continents, and almost half as much as all of China. If we accept the widely quoted statistic that the construction sector contributes 40 percent to global CO2 emissions, then we can safely assert that over the course of its history, Germany’s construction sector alone has consumed about as much as all of Africa combined.

Certainly, the tide has “turned”, so to speak. Based on the year 2018, Germany’s share of global CO2 emissions is, in the end, “only” half as high as that of Africa, which has only a measly 1.3 billion inhabitants compared to Germany’s 83 million. China is catching up by leaps and bounds, releasing more than ten times as much CO2 in 2018 than Germany. However, the “argument” that our “little” country can’t make a difference anyway when compared globally to giants like China or India is wrong, particularly from a historical perspective. (1750–2017: India 3%, Germany 5.73%. 2018: India 7.12%, Germany 1.93%. Population of India: just under 1.4 billion.)

To say that we should actually pay “CO2 reparations” may be putting it harshly. However, given the numbers and the consequences for those who aren’t lucky enough to live in the so-called First World, this is certainly appropriate. For we know that those consequences may be readily compared to the consequences of war.

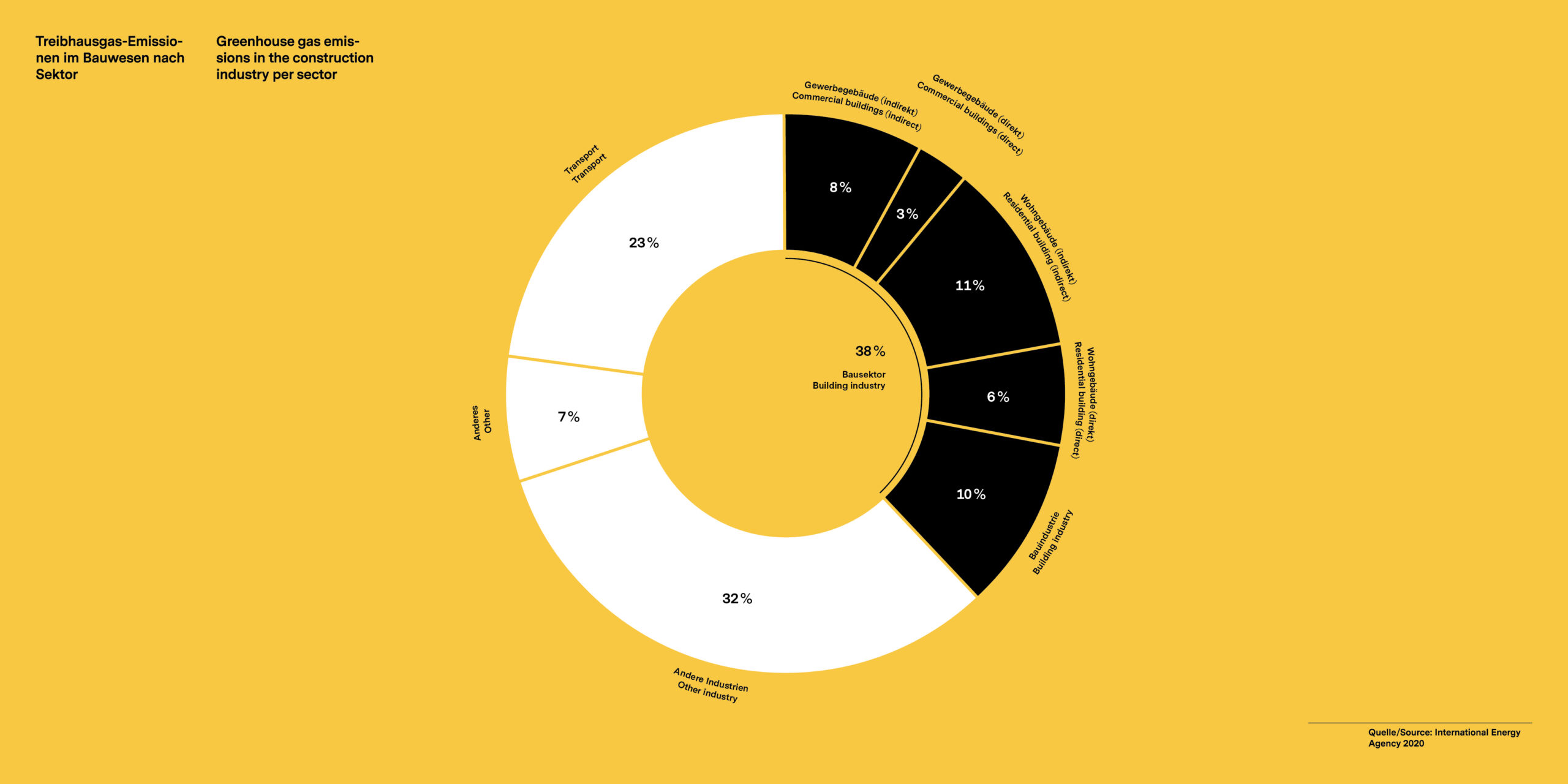

“We” – that’s Germany, certainly, but “we” is also and above all the “we” who build and commission others to build, meaning we architects, we in the construction industry, we building-makers. Sorry to say, “we” are the worst. We’re responsible for at least 40 percent of all CO2 emissions on our planet, but it’s actually probably more than that – when it comes to this pivotal figure, there’s an almost Babylonian confusion of languages that can sometimes be unintentionally hilarious.

I can’t speak for all German architects. Nor can I deny that my use of words like “uniform” or “streamlined” is unfair, in that it may imply a degree of deception or cowardice. When everyone – including me! – is saying more or less the same thing, that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s wrong. Convergence is compelling and rational. Convergence is good! The blue shark is the seventh fastest fish in the sea. Obviously its form is effective, and form follows function.

But I wouldn’t have any backbone if I pretended that I really had a resilient stance on sustainability. I know that I, that the vast majority of us, aren’t rigorous enough, and I also know that I don’t feel equipped for that rigor (as yet). All of us, as qualified as we may well be, are aware of this. We’re out of time. Most of us heard the shot a long time ago, perhaps too long ago. What we’ve been hearing for years, I believe, is no longer the shot, but its echo. Is it possible that we’ve come to confuse the two? I for one feel as though I’m in a self-congratulatory echo chamber where my knowledge of sustainability – despite or because of the constant flood of new knowledge about techniques and materials – seems to be decreasing rather than increasing. This feels like racing while standing still.

I no longer have a stance because I no longer believe that I can allow myself one. What I do have – and I’m certainly not alone in this – is an assumed posture. For me, “stance” needs to be stripped of its quotation marks, just as “sustainability” does. Instead of quoting myself and others, I have to find a new stance for myself and my employees – most importantly, together with them! When I heard the shot again and again over the past few months, I realized that I must first set the stage for finding this stance. This means preparing for the quest. We’re documenting, accompanying, and supporting this quest and its prerequisites with our series of publications, Der Nachhalt.

To whomever might ask me now about my stance, I can only say that for the time being, my stance on sustainability consists of developing a stance on sustainability, and The Prologue is the beginning of this development.